The adult human body contains around 207 bones. Like any system in the body, it’s prone to damage, but did you know that bone is one of the few tissues that can heal without forming a fibrous scar?

Last week we examined the various processes involved in healing a minor wound such as a scrape or a cut. Now let’s really get under the skin and have a look at the self-repair mechanisms that are activated once a bone is damaged or fractured.

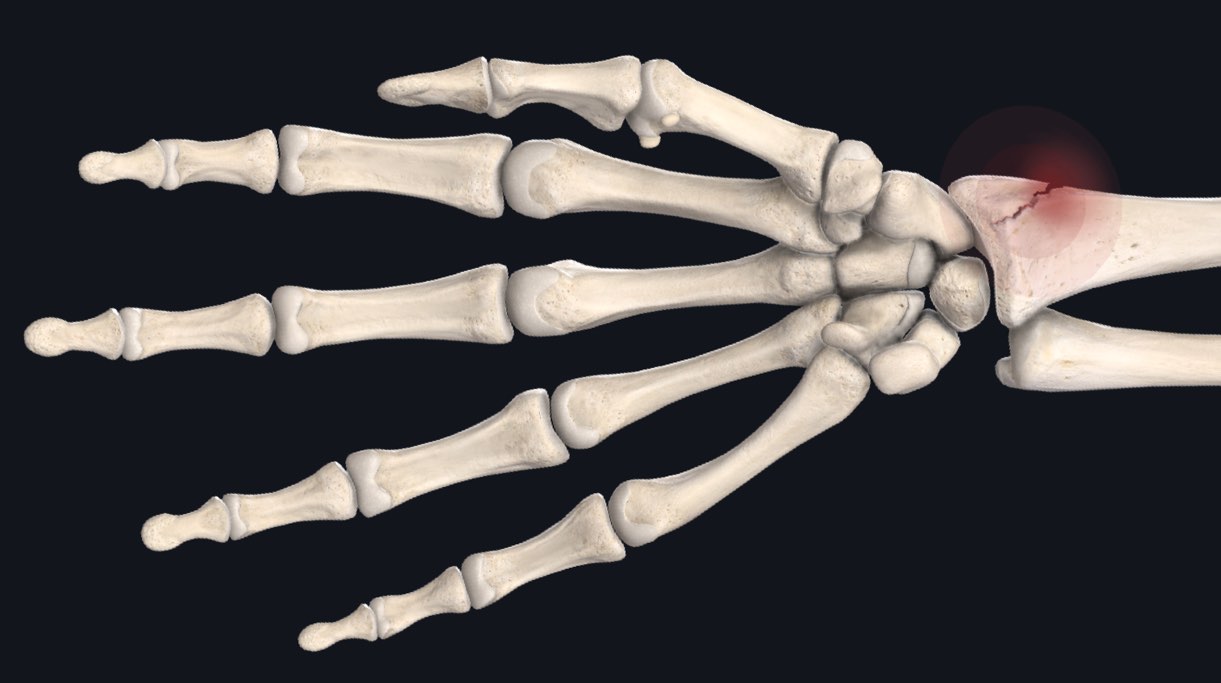

1. Hematoma formation

This occurs immediately after damage occurs. Blood vessels are disrupted, leading to bleeding and the formation of a clot. Typically within 6-8 hours, the clot has formed what’s known as a fracture hematoma. This clotting reduces the blood supply to many of the cells in the area of injury, and as a result these cells die.

2. Bone generation

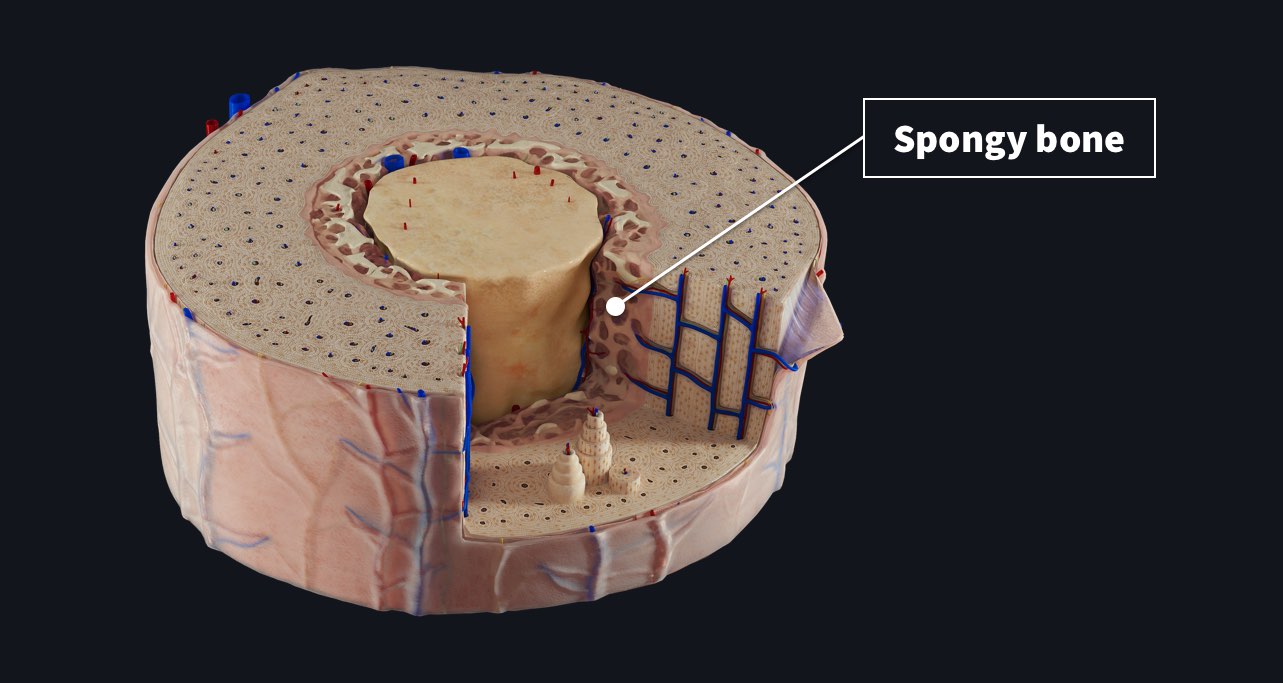

White blood cells are then recruited to remove any dead cells and debris. Fibroblast and osteoblast cells are also recruited, stabilising the fracture. The fibroblasts form granulation tissue around the broken ends of the bone while the osteoblasts begin to synthesise spongy bone, forming fibrocartilaginous callus.

3. Bony callus formation

In the weeks that follow, the fibrocartilaginous callus is replaced by a bony callus known as cancellous bone. This process is facilitated by endochondral ossification. The remaining cartilaginous callus is reabsorbed in the surrounding tissues and begins to calcify. Newly formed blood vessels proliferate.

4. Bone remodelling

The bony callus then undergoes repeated remodelling. This process relies on a balance of resorption by osteoclasts and new bone formation by osteoblasts. This step may occur over several months until the bone has returned to its original state and even after, the bone may remain uneven for years.

Dive right under the skin and learn the composition of bone tissue, with our advanced 3D microanatomy model of the bone tissue, one of 15 detailed models on the platform. Try it for FREE today.